For all its concern with change in the present and future, science fiction is deeply rooted in the past and, surprisingly, engages especially deeply with the ancient world. Indeed, both as an area in which the meaning of “classics” is actively transformed and as an open-ended set of texts whose own ‘classic’ status is a matter of ongoing debate, science fiction reveals much about the roles played by ancient classics in modern times.

Classical Traditions in Science Fiction—edited by Brett M. Rogers and Benjamin Eldon Stevens—is the first collection dedicated to the rich study of science fiction’s classical heritage, offering a much-needed mapping of its cultural and intellectual terrain. Available February 9th from Oxford University Press, this volume discusses a wide variety of representative examples from both classical antiquity and the past four hundred years of science fiction, exposing the many levels on which science fiction engages the ideas of the ancient world, from minute matters of language and structure to the larger thematic and philosophical concerns.

Below, Vince Tomasso explores the role of classical antiquity, myths, and tradition in Battlestar Galactica.

Classical Antiquity and Western Identity

in

Battlestar Galactica

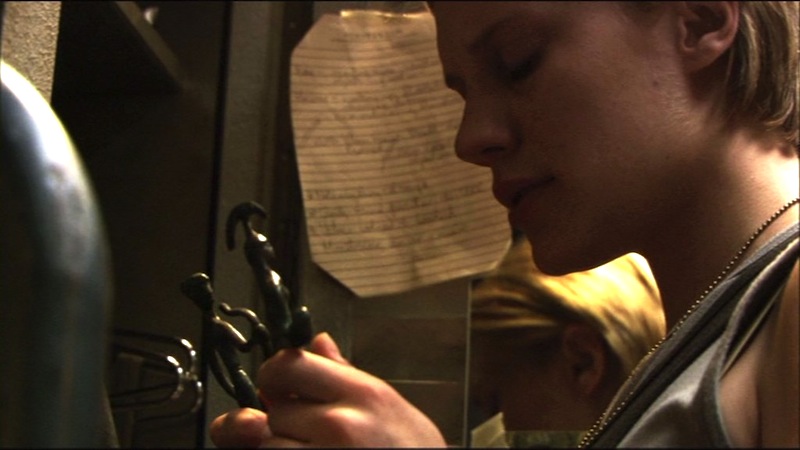

In the first season of the science fiction (SF) television series Battlestar Galactica (2003–2009 [BSG]), Lieutenant Kara “Starbuck” Thrace travels to the planet Caprica in order to obtain the Arrow of Apollo (“Kobol’s Last Gleaming, Parts I and II,” 1.14–15).[1] She undertakes this mission on the orders of President Laura Roslin, who, inspired by a prophecy in the sacred Book of Pythia, believes that the Arrow will show them the way to Earth and, ultimately, the salvation of humankind. Caprica is a charred wasteland, having been devastated by nuclear weapons used by the Cylons, the robot civilization that annihilated much of human society at the start of the series. The Arrow is housed in the Delphi Museum of the Gods, which Thrace finds in ruins: rubble strewn on its front steps and throughout its galleries, exhibits smashed and mutilated, and broken pipes leaking water. It has become a tomb for religious artifacts, many of which, though badly damaged, are vaguely identifiable as statues and vases from classical antiquity.[2] From these ruins Thrace is able to retrieve the Arrow (as seen in Figure 11-1), which is a key step in the teleology of the series: the search for an inhabitable planet and the resolution of the endless cycle of violence between humans and Cylons.

This scene demonstrates how BSG meditates on the construction and meaning of human, and more particularly Western, identity via classical antiquity. Humans in the series articulate their identities in part through religion, which is predicated on what the series’ audience associates with classical myths. Using classical myths in this way creates what literary critic Darko Suvin calls “cognitive estrangement,” a central aspect of the SF genre as he defines it: “SF is, then, a literary genre whose necessary and sufficient conditions are the presence and interaction of estrangement and cognition, and whose main formal device is an imaginative framework alternative to the author’s empirical environment.”[3] “Estrangement” means that the text’s narrative universe is distanced from the audience’s knowledge of their own world—that there are some similarities with the “real” world, but also a “new set of norms.”[4] “Cognitive” means that the estrangement impels the audience to reflect on the differences between their world and the narrative world. BSG’s cognitive estrangement is achieved via a setting distant in time and place from the audience’s own, populated by beings whose culture and society are both similar to and different from the audience’s, as well as a variety of technological factors that have parallels in the audience’s world, especially space travel and the creation of artificial intelligence that becomes self-aware. Indeed, the finale strongly implies that the latter process is already underway in the audience’s contemporary world through footage of various kinds of robots, including one that mimics the human form and appearance very closely.[5] In short, BSG’s cognitive estrangement causes the audience simultaneously to identify with and to be distanced from the series’ human culture.

In this chapter, I argue that BSG uses cognitive estrangement to give its audience a broader perspective on themselves and their Western identity, and that this perspective is informed by the series’ message that the mythic approach to the universe, rather than the cognitive one, will save humanity.[6] Classical antiquity is thus positioned in a complex way as both a source of salvation through its myths, and a source of destruction through ancient Greece’s cognitive inquiry and Rome’s decadence. This attitude reflects uncertainties about the Western tradition and its future role in the formation of identity.

BSG aired for four seasons on the SyFy cable channel from 2003 to 2009. It is a reimagining by Ronald Moore of a 1978 television series of the same name and premise that was created by Glen Larson; this chapter will focus on the later series exclusively.[7] The narrative of Moore’s series begins with the destruction of a human civilization called “the Colonies” by the Cylons, a society of robotic organisms that were created by humans as servants. The nuclear attack is the culmination of several years of conflict between the two sides after the Cylons became self-aware and waged war on the Colonies. The series chronicles the journey of the attack’s survivors in a fleet of spacecraft composed of the military ship Galactica and a number of civilian ships as they try to find another inhabitable space while surviving the pursuit of the Cylons.

The Colonials are polytheists, worshipping beings that they call the Lords of Kobol, whose basic attributes, spheres of influence, and relationships with one another are almost identical to those that are attributed to the deities depicted in classical myths. For instance, the call sign of Lee Adama, a high-ranking Colonial officer, is “Apollo,” whom another character identifies as a son of Zeus, “good with a bow, god of the hunt, and also of healing” (“Bastille Day,” 1.3); similarly, various classical texts also attribute these characteristics to the Greek and Roman god Apollo.[8] Gods mentioned and/or directly worshipped in the series are Aphrodite, Apollo, Ares, Artemis, Asclepius, Athena, Aurora, Hera, Poseidon, and Zeus (which we see, for example, in Figure 11-2). Characters call these deities by their ancient Greek names almost exclusively, but in a few cases they use the Roman equivalent. “Aurora” is the Roman name for the goddess of the dawn (Grk. “Eos”); and although characters most often refer to the king of the gods as “Zeus” and the god of war as “Ares,” in a few cases they use the Roman equivalents “Jupiter” and “Mars.” These exceptional cases could be mistakes made by the producers and writers, but they also demonstrate that in American popular culture ancient Greece and Rome are often conflated. For this reason I speak of BSG’s engagement with classical antiquity, classical myths, and the classical tradition generally rather than with ancient Greece specifically.

The series’ connection with classical antiquity extends beyond narrative to practice. Oracles—Colonial religious personnel who are integral to the teleology of the series—articulate knowledge received from the Lords of Kobol in much the same way as oracles did in classical myth and ancient life.[9] In the episode “Exodus Part I” (3.3), the Colonial oracle Dodona Selloi plays an important role. Her name is derived from the ancient site of an oracle of Zeus in northwestern Greece, and the names of the priests who worked there. The Greek warrior Achilles describes Dodona in Book 16 of Homer’s Iliad (Il.): “Zeus, Pelasgian lord of Dodona, dwelling far away, ruler of wintry Dodona, around you the Selloi dwell, oracles with unwashed feet who sleep on the ground” (ΖεῦἄναΔωδωναῖεΠελασγικὲτηλόθι ναίων / Δωδώνης μεδέων δυσχειμέρου, ἀμφὶδὲΣελλοὶ/ σοὶναίουσ’ ὑποφῆται/ἀνιπτόποδεςχαμαιεῦναι; 233–235). Dodona Selloi connects Colonial spirituality and the classical legacy it represents with the future survival of mankind when she prophesies about Hera Agathon, a human-Cylon hybrid child who will be central to the conclusion of the series. Although long deceased by the time the series begins, the Pythia is another oracle whose advice Laura Roslin, the President of the Colonies, follows ardently. The Pythia’s writings in the Sacred Scrolls guide Roslin, just as in antiquity the Pythia’s prophecies at Apollo’s temple at Delphi in northern Greece guided visiting suppliants; they are also similar to the Sibylline books consulted by the Romans.

The Lords of Kobol and the myths about them are important aspects of Colonial identity for many characters in the series, including non-humans. To Sharon Agathon, a Cylon who falls in love with, marries, and has a child with Colonial captain Karl Agathon, Colonial religion is a bridge between the world that she wishes to leave and the one she wishes to enter. In the second season, she joins Karl on the Galactica but is promptly thrown into the brig because the crew do not trust her. When Commander William Adama realizes that Sharon can be a useful ally in a rescue operation, he officially commissions her as an officer (in the episode “Precipice,” 3.2). In spite of this, the majority of the human crew still does not trust her, and throughout the rest of the series Sharon suffers from periodic racist attacks, though it is clear that she has gained some status in human eyes when she takes on a traditional pilot call sign. In the episode “Torn” (3.6), Karl solicits a call sign for his wife from their fellow officers. Sharon settles on Brendan Costanza’s proposal of “Athena”: “You know—the goddess of wisdom and war, usually accompanied by the goddess of victory?” This moment demonstrates the important role that Colonial religion and myth can play in some segments of Colonial society. Before this moment, Sharon was counted among the humans’ antagonists, a status that begins to change with Adama’s official recognition of her as an ally. Yet she embraces her new human identity fully only when she takes on the name of a divinity worshipped by her race’s enemies. The question of belief is irrelevant here; what matters is that Colonial myths are supporting the formation of a human identity; thus they are cultural markers rather than markers of belief, necessarily.

Not all Colonial officers view these myths positively, and there is a wide spectrum of belief among both the civilian and military populations, from atheists like Commander William Adama, to ardent believers like Roslin, to the cautiously faithful like Thrace, to opportunists like Gaius Baltar. Some characters vociferously assert their skepticism of religion and the myths that accompany it. When Roslin, guided by the mythic hermeneutic, suggests that a myth about the Arrow of Apollo detailed in Colonial scripture will be the key to the fleet’s salvation, in keeping with the cognitive hermeneutic Adama protests, “they’re just stories, myths, legends. Don’t let it blind you to the reality we face” (“Kobol’s Last Gleaming,” 1.12). Despite his dim view of the truth-value of such narratives and skepticism toward the mythic approach that they support, however, Adama nevertheless uses these same stories to achieve his own ends. In the second episode of the miniseries, he recites the legend of Earth from the Book of Pythia in order to give the fleet purpose, despite his later revelation to Roslin that he does not believe in the planet’s existence.[10] Whatever the beliefs held by individuals, Colonial myths are used to direct the teleology of the series, demonstrating that they are an important and defining part of human culture in the series.

These references to classical myth are recognizable to the target audience on some level as a result of the Western production and reception context of BSG. SyFy is an American cable channel owned by the large American media conglomerate the National Broadcasting Company (NBC). The creator of the series, Ronald Moore, is an American, as are the writers. Most of the cast members are North Americans, and most of the filming was done in British Columbia, Canada. The target audience of SyFy is primarily in the English-speaking Western world: the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia. Audiences in these countries tend to be somewhat familiar with classical myths through modern retellings like Edith Hamilton’s Mythology (1942), Ingri and Edgar Parin d’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths (1962), and Bernard Evslin’s Heroes, Gods, and Monsters of the Greek Myths (1966), which are used frequently in secondary and post-secondary education.[11] The ubiquity of classical myths in modern popular culture similarly attests to their popularity.[12]

BSG’s inclusion of classical myths into the belief system of a society as technologically advanced as the Colonies allows the series to explore the ontology and future of humanity via the conflict between the mythic hermeneutic (represented by the classical tradition) and the cognitive hermeneutic (represented by SF). The classical tradition, in which cultural products created after antiquity refer to or adapt the worlds of ancient Greece and Rome, on the surface contrasts with SF. Whereas the former looks to the past in order to bring the present into better focus, SF speculates based on the scientific methodology so characteristic of the modern period to make sense of the present moment.[13] While some scholars trace the roots of SF as far back as the Greek writer Lucian’s second century c.e. satire True Histories (and in a few cases, to the one of the oldest Greek texts we have, Homer’s Odyssey), in modern popular culture SF is usually associated with modern scientific and technological advancement.[14] Although, as the chapters in this volume show, SF has deep connections with antiquity,[15] for modern audiences the classical tradition and SF nevertheless appear to be on opposite ends of history, since the latter is predicated on the conditions that belong to or stem from the audience’s own moment, whereas the former is predicated on the cultural conditions that prevailed thousands of years ago.[16] I want to stress that popular culture often imposes this opposition between the classical tradition and SF; the two modes of thought are in fact quite similar, since both strategies reflect the concerns of the present by reflecting on another time period.[17]

This artificial division between classical tradition (ancient) and SF (modern) is sometimes conceptualized as a series of negotiations that occurs within the SF genre itself between two approaches to understanding what it means to be human in the wider universe. The mythic hermeneutic is rooted in knowledge obtained through supernatural sources, religious practice, and tradition, while the cognitive hermeneutic derives from empirical knowledge, scientific methodology, and progress. Mendlesohn argues that, in the twentieth century, SF “treated [religion] . . . with at best polite contempt: religion was essentially of the ‘Other,’ the backward and primitive. . . .”[18] In science fictional receptions of classical antiquity, this conflict is often presented as the myth-obsessed ancient Greek and Roman cultures, which worshiped fickle and jealous deities, versus cognitive modern cultures, which are “enlightened” about the nature of the universe through empirical observation. Of course this dichotomy is not an accurate representation of reality—after all, ancient Greek philosophy and science were the precursors of modern scientific methodology, and likewise there are modern myths—but this is often the popular perception of the conflict in SF.

An example is the 1967 episode of Star Trek: The Original Series “Who Mourns for Adonais?” (2.2), in which Captain Kirk and crew encounter a being that claims to be the god Apollo.[19] The crew determines that Apollo is a member of an alien race that visited Earth 5,000 years previously and used their technological knowledge to elicit worship from the ancient Greeks. In the conclusion of the episode, Kirk disavows Apollo, and the alien perishes.[20] After Apollo’s death, Kirk reflects that the Greek “gods” were important: “Much of our culture and philosophy came from a worship of those beings.” In this vision of the glorious and progressive future, humans have no more place for the mythic approach, despite the acknowledged fact that this system eventually allowed culture (and by implication, science) to advance. Ancient Greek religion and myth are important stepping stones that humanity no longer needs—indeed, they literally threaten to halt the Enterprise’s mission “to seek out new life and new civilizations” and to trap Kirk and company in the unenlightened and servile past.

“Who Mourns for Adonais?” is pertinent to the present argument because of its influence on Ronald Moore, the creator of the reimagined BSG. Moore was a fan of Star Trek as a young man and became a writer for three subsequent series, Star Trek: the Next Generation (1987–1994), Deep Space Nine (1993–1999), and Voyager (1995–2001).[21] As a result, he studied and absorbed Star Trek’s attitudes and philosophies, and BSG is in part his response to those worldviews. Whereas Star Trek in general praises the cognitive hermeneutic over the mythic one, Moore’s series does the reverse; not only is the cognitive approach viewed negatively because it is responsible for the creation of the Cylons and the near-total destruction of humanity, but the mythic approach is an integral part of the series’ teleology.

The mythic hermeneutic in BSG is advocated by a group of Colonials, the most prominent of whom is Laura Roslin, the President of the Colonies. She uses Colonial myths, via scripture and artifacts, to make sense of the post-apocalyptic universe. The series consistently validates the mythic mode of interpretation because it plays a crucial role in the search for and ultimate discovery of a new home after the destruction and occupation of the Colonies. By contrast, the cognitive hermeneutic is embraced by William Adama, the military commander of the fleet, who explicitly rejects myth as an approach to solving problems and understanding humanity’s place in the universe.[22] The exponents of these two extremes frequently clash over how to proceed. The opening of this chapter contains an example of this clash: Roslin is guided by the priestess Elosha to seek the Arrow of Apollo that the Sacred Scrolls claim will point the way to Earth (“Kobol’s Last Gleaming, Part I,” 1.12). Adama forbids this, but Roslin secretly orders Lieutenant Kara Thrace to retrieve the Arrow. Because she directly contravened his orders and subverted one of his officers, Adama removes Roslin from the presidency, and the conflict between these two characters is a major plot line in the first half of the second season. Eventually, a team from the Galactica successfully uses the Arrow to open the Tomb of Athena on the planet Kobol (“Home, Part II,” 2.7), which correctly identifies the next stop in the search as the Eye of Jupiter, an astronomical phenomenon that directs the Colonials to the Ionian Nebula, a supernova remnant near Earth. These events validate the mythic hermeneutic that Roslin ascribes to, as opposed to the cognitive approach that Adama propounds. Without the Sacred Scrolls, the Arrow of Apollo, and the Eye of Jupiter, Earth would never have been discovered.[23] In fact, without Colonial myth and religion, Earth might have never been a goal for the fleet in the first place. There is no empirical knowledge about the existence of Earth at the opening of the series; it is a matter of faith in the Sacred Scrolls, the Colonials’ book of scripture, which contain the legend of Earth.

The cognitive hermeneutic loses out in the struggle between Adama and Roslin, and this valorization of the mythic hermeneutic occurs in many other places in the series. Science is responsible for the major problems of the narrative: scientists created the Cylons, nuclear weapons annihilated Colonial civilization, and the Colonies’ most prominent scientist, Gaius Baltar, allowed the Cylons to penetrate Colonial defenses.[24] All of these negative connotations, combined with the success of Roslin’s mythic hermeneutic, lead to a controversial move in the finale. Lee Adama pathologizes technology and boldly suggests that the Colonials destroy all of their equipment and begin their new lives on Earth tabula rasa. This suggestion represents the ultimate triumph of mythic over cognitive hermeneutics: “our brains have always outraced our hearts. Our science charges ahead, but our souls lag behind. Let’s start anew” (“Daybreak, Part II,” 4.20). Following Lee’s advice, the Colonials send all of their technology into the sun and provide the indigenous humans with language (“we can give them the best part of ourselves”)—and presumably the culture that is implied by language. This solution to the considerable problems posed throughout the series has angered many critics, but in some ways it is a valid response to the frustrating cycle the Colonials find themselves trapped in.[25] If technology is what renews the destructive cycle, it is logical that the cycle will be broken if technology is abandoned. The final moments of the finale, in which modern American society is on the same brink of total collapse because of its heedless pursuit of (robotic) technology, call into question the success of Lee’s plan. In BSG’s vision of history, the route to humanity’s salvation is the mythic one, not technological progress—even though the latter resulted from the materialist inquiries made by Greek philosophers who participated in the same culture that also invested in the mythic approach. Although the Colonials attempted to jettison technology, humans eventually discovered it again, due in part to ancient Greece’s contributions. By locating humanity’s downfall in science and technology and its salvation in spirituality, BSG positions the classical past as simultaneously solution and problem.

The series creates this picture of classical antiquity by causing its audience both to identify with and to be distanced from Colonial religion. Identification encourages the audience to see similarities between themselves and the Colonials, while distancing provides them with a broader perspective on their own identities. We have already seen how Colonial religion creates identification through its strong associations with classical myth, but identification is also achieved through the religion’s differences from ancient Greek and Roman religions. While classical myths are familiar to Western audiences, ancient religions, with their extensive use of sacrifice and lack of organizational structures and dogmatic religious texts, are not. Colonial religious practices are modeled on those of modern Judaism and Christianity. For instance, the personnel consists of priests, priestesses, brothers, and sisters; priests wear stoles and brothers wear black habits; and Galen Tyrol sees Brother Cavil for a version of confession (“Lay Down Your Burdens Part I,” 2.19). Moore and his team did not use classical religious practices as the basis for Colonial religious practices, probably because doing so would distance the audience too much. BSG’s combination of classical myths with modern religious rituals incorporates classical antiquity into a future human culture that Moore’s audience could recognize and identify with to some extent.[26] Colonial culture is not ancient Greece or Rome, nor is it any modern Western culture; it is an amalgam of all of these cultures and thus signifies Western-ness on an abstract level.

The audience is distanced through Colonial religion’s most central feature, polytheism. The Cylons, by contrast, are monotheists: the Cylon God is omnipotent and omniscient, his worshippers spread his gospel, and he is equated with love and salvation from sin.[27] Because Western cultures are heavily influenced by Judeo-Christian thought—whether audience members identify themselves as members of those faiths or not is irrelevant—this aspect of Cylon culture creates some measure of identification. Both Colonials and Cylons thus evoke identification and distancing, a situation that Marshall and Potter analyze in terms of American and Muslim identities in the first decade of the twenty-first century.[28] They conclude that Colonials and Cylons embody different aspects of these two groups at different points in the series, a situation that destabilizes the audience’s assumptions about their own identities. This is similar to what I am saying about the series’ use of cognitive estrangement through classical antiquity: the audience’s identification with and estrangement from Colonial culture result in a broadened perspective on the audiences’ Western identities.

Sandra Joshel and her co-authors write in the introduction to Imperial Projections that this principle also holds true for cinematic receptions of ancient Rome: “popular representations allow audiences simultaneously to distance themselves from that past and to identify with it.”[29] This similarity makes SF’s receptions of the classics as worthy of analysis as cinema’s, but it is important to note that the two phenomena are not exactly parallel. Joshel’s cinematic receptions allow for both identification and estrangement in order to confirm the present audience’s notions of self, whereas SF (and BSG’s reception of antiquity) does this in order to cause the audience to reexamine their preconceived ideas about their own identities. The series encourages its audience to both identify with and be estranged from the classical tradition to give them a different perspective on the Western tradition that informs their identities. Cognitive estrangement thus paves the way for the audience to accept one of the ultimate messages of the series: that humanity must embrace a mythic approach to the universe in order to break the historical cycle of destruction, which has been exacerbated by the cognitive approach based on science and technology.

Although the Colonials’ mythic hermeneutic points the way to a future, it cannot ensure that future because it is incapable of ending the cycle of violence by itself. Although science certainly contributed to it, the conflicting religious systems of Cylons and Colonials are also at the heart of the problem. The solution, the series ultimately posits, is hybridity, which is embodied in Hera Agathon, the child of Colonial Karl Agathon and Cylon Sharon. Despite the hybridity of Hera’s human and Cylon DNA, her name derives solely from Colonial myth and culture: her first name is identical with the name of Zeus’ wife, and her last name means “good” in ancient Greek.[30] We learn in the finale that Hera is absolutely critical to the survival of humanity. In “Daybreak, Parts I and II” (3.19–20), the Colonials reach Earth and merge with the native population, a very early form of Homo sapiens. The narrative skips ahead 150,000 years and reveals that Hera was the “mitochondrial Eve,” an ancestor of modern humans. Hera is thus a major part of the solution to the conflict between humans and machines and the interminable cycle of destruction in that she merged the genes of Cylons and humans into an indistinguishable common heritage.

Despite her name’s pedigree, Hera is far from a pure embodiment of Colonial spiritual tradition. Her mixed blood makes her an alteration of tradition, a realignment of the past to accord with the exigencies of the future, which is necessary if there is to be a future at all for humans or Cylons. The fact that all of this took place in human prehistory—with the implication that ancient Greece and Rome somehow received aspects of their culture from the Colonial and Cylon survivors—demonstrates how Westerners have moved and continue to move away from Colonial religious tradition toward technological hedonism and destruction. This swerve from tradition is embodied in the erasure of Hera’s original name by modern scientists, who replaced it with two new cultural referents, an adjective derived from a microscopic structure in cells that is discernible only with advanced technology, and the name of the first woman in the Old Testament. “Eve” may suggest that there is a glimmer of hope that Colonial tradition has not been lost completely, but many scientists express regret that their observation was ever associated with that name.[31] Hera’s rechristening suggests that modern humans have forgotten the Colonials’ decision to reject the cognitive and embrace the mythic and are no longer aware of the cultural compromise that produced Hera. Her name and function have been lost to time, and with this loss, so, too, the ability to recognize humanity’s dark past and compromised future.[32]

In the final moments of the last episode, two mysterious “angel” figures, who claim to be servants of an omnipotent being and who are identical in appearance to Baltar and Cylon model Six, stroll through a modern city and ruminate on the fate of humanity. “All of this has happened before—” Six begins, and Baltar finishes her sentence, “—but the question remains: does all of this have to happen again?” This exchange recapitulates the central question of the series: does the mythic, represented in the series by the classically inspired Colonial religion, weigh down and destroy humanity, rendering it incapable of breaking out of the historical cycle of violence, or does it have the power to save? Baltar is skeptical that the modern Earth can survive, referring to the destroyed planets Kobol, Earth, and Caprica, but Six is hopeful (“Let a complex system repeat itself long enough and eventually something surprising might occur”)—which is ironic, given the Corinthian capitals clearly visible behind her. This scene reminds us of the important part that classical antiquity plays in BSG’s major themes. On one hand, classical/Colonial myths are indispensable for locating a place where life can continue. On the other hand, classical antiquity is revealed to be the cause of humanity’s inability to escape the cycle, not only through the clash of Colonial and Cylon civilizations, but also through the scientific and technological advances of ancient Greek thinkers and the decadence of the Roman Empire.[33]

To break out of this destructive cycle, BSG suggests, humanity must embrace a mythic hermeneutic and hybridize its traditions, as well as reject the technology that leads to arrogance and decadence. Deriving many of its elements from classical myth, Colonial religion creates cognitive estrangement by anchoring its audience’s identities in their Western heritage, while also distancing them by depicting these myths as the basis for the polytheistic religious practice. Through cognitive estrangement, BSG seeks to give its audience a broadened perspective on themselves as well as argue the necessity to return to a mythic tradition. The series never explicitly states why humanity diverged from the path towards the mythic set by the Colonials, but an inevitable conclusion is that the classical civilizations were partly responsible for the swerve. Colonial spirituality gave way to technology and science, which were developed in the West by Greek empirical thinkers and philosophers, most famously on the western coast of Asia Minor in the sixth century b.c., and to the hedonistic decadence of the Roman Empire.[34] The series thus presents a deeply conflicted picture of classical antiquity and its legacy as vital for Western identity, culture, and continued existence, and simultaneously as part of the cycle of conflict and destruction.

“Antiquity and Western Identity in Battlestar Galactica” excerpted from Classical Traditions in Science Fiction © 2015

Figure 11-1

Kara “Starbuck” Thrace prepares to take the Arrow of Apollo from its display in the Delphi Museum of the Gods. From Michael Rymer, dir. 2005. “Kobol’s Last Gleaming Part II,” Battlestar Galactica, NBC Universal.

Figure 11-2

Kara “Starbuck” Thrace prays to statuettes of Artemis and Athena. From Brad Turner, dir. 2004. “Flesh and Bone,” Battlestar Galactica, NBC Universal.

[1] I would like to thank Brett M. Rogers and Benjamin Eldon Stevens for organizing the innovative panel (American Philological Association, San Antonio, Texas, 2011) from which this chapter originated, and for making helpful comments on drafts. Audience members at that meeting and at a version of this chapter presented at Stanford University responded thoughtfully. Mark Pyzyk, Toph Marshall, and Erin Pitt read and commented on drafts at various stages. Two anonymous readers for the Press raised stimulating questions and issues. Any remaining infelicities are my own.

[2] This depiction of classical ruins is a prevalent motif in SF; see Brown (2008: 416–422).

[3] Suvin (1979: 7–8). Despite Suvin’s language, SF is not limited to literature; see Roberts (2006a: 2), who argues that the genre is a “cultural discourse” that includes literature, television programs, films, comic books, and video games.

[4] Suvin (1979: 6).

[5] One of the pieces of footage is stamped with the MSNBC logo, a global television news channel in the audience’s world.

[6] I have borrowed the terms “mythic” and “cognitive” from Suvin’s definition of the SF genre’s approach to the universe (1979: 7): “The myth is diametrically opposed to the cognitive approach since it conceives human relations as fixed and supernaturally determined. . . . Conversely, SF . . . focuses on the variable and future-bearing element from the empirical environment. . . .”

[7] Caprica (2010) and Blood and Chrome (2012) are prequel series to the reimagined BSG that exist within the same narrative continuity but deal with somewhat different issues; this chapter does not take them into account.

[8] Another instance of this phenomenon is in the episode “The Passage” (3.10), when a Cylon Hybrid calls the Eye of Jupiter “the eye of the husband of the eye of the cow.” Gaius Baltar deduces that the latter part of this riddling description alludes to “Hera, sometimes referred to as ‘cow-eyed Hera’.” This is a common description, or epithet, of the goddess in classical texts (βοῶπις in Greek), which demonstrates the complex nature of Moore and his team’s engagement with classical antiquity.

[9] For an in-depth look at oracles in the ancient Greek world, see Burkert (1985: 114–118).

[10] Ironically, Pythia’s prophecy about Earth turns out to be true in the final episodes.

[11] Meckler (2006: 10, 176).

[12] Recent, high-profile film releases include Clash of the Titans (Leterrier), Immortals (Singh), and Wrath of the Titans (Liebesman). Classical myths have also formed the basis for highly successful television programs like Hercules: the Legendary Journeys (1995–1999) and Xena: Warrior Princess (1995–2001).

[13] Franklin (1978: vii) argues that the SF genre results from the mindset created by the rapid and continual scientific and technological progress at the start of the Industrial Revolution. Cf. Suvin (1979: 64–65): “[t]he novum is postulated on and validated by the post-Cartesian and post-Baconian scientific method” [emphasis in the original].

[14] See Suvin (1979: x, 87, and 97–98) and Georgiadou and Larmour (1998: 45–48) for assessment of and further bibliography on Lucian’s place in science fictional genealogies. See also Rogers and Stevens (2012a: 141–142), who argue that we might search for common strategies between classical texts like Homer’s Odyssey and Lucian’s True Histories and SF, rather than a literal origin. For a connection between Lucian and a particular modern exemplar, H. G. Wells, see Keen (this volume, chapter four).

[15] Witness the subtitle of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, on which see Rogers and Stevens (2012a: 127–129); cf. their introduction to this volume. I would argue however that part of the pleasure for the reader here is the frisson generated by the juxtaposition of title and subtitle.

[16] Bukatman (1993: 4) further links technology to the American ideal of progress: “Technology . . . defines the American relation to manifest destiny and the commitment to an ideology of progress and modernity.”

[17] Cf. the formulation of the relationship between past, present, and future in SF by Rogers and Stevens (2012a: 129): “modern SF has, from its very beginnings, as it were looked forward to the future and around at the present in part by looking further back. . . .” (emphasis mine). Cf. also Brown (2008: 416), who states that there is “an obvious ostensible mismatch between the ‘classics’ (high status, elite, ancient) and SF (low status, popular, modern) . . .” (emphases mine).

[18] Mendlesohn (2003: 264). Cf. Roberts (2006a: 3), who locates the genesis of SF in the conflict between science and religion: “The specificity of this fantasy is determined by the cultural and historical circumstances of the genre’s birth: the Protestant Reformation, and a cultural dialectic between ‘Protestant’ rationalist post-Copernican science on the one hand, and ‘Catholic’ theology, magic and mysticism, on the other.” Roberts also identifies the genre along a continuum spanning the avowedly realistic (“hard SF”) and the completely mystical (fantasy). The conclusion of BSG causes the series to fall closer to the latter category, but it was still very much on the SF continuum for the majority of its run.

[19] The title of the episode is derived from Percy Bysshe Shelley’s 1821 poem “Adonais.” Some scholars have thought that Shelley’s title is a merging of the name “Adonis,” the Greek youth who is a lover of Aphrodite and killed out of jealousy by Ares, and the Hebrew word “Adonai,” which means “Lord;” see, e.g., Wasserman (1959: 311–312). On the episode, see further, Kovacs (this volume, chapter nine).

[20] Kirk’s rejection of Apollo is mysterious: “Mankind has no need for gods. We find the one quite adequate.” The philosophy implicit in this statement is never elaborated, but one possibility is that the writer/producers formulated it to placate the majority Christian audience members while also expressing a kind of pantheistic view of the universe; cf. Asa (1999: 45), who dismisses the implications of the comment. The creator of the series, Gene Roddenberry, was in any case an avowed atheist; see Pearson (1999: 14).

[21] Cf. Porter and McLaren (1999: 2–3).

[22] Pache considers classical reception in the series primarily with regard to the romantic relationship between Adama and Roslin. She analyzes the figure of Adama through Aeneas, and of Roslin through Dido, to argue that BSG is “a feminized version of Vergil’s Aeneid that focuses on love and compromise as the basis of the new empire” (2010: 132). Other sources for aspects of BSG have been identified in Hesiod’s Theogony and Works and Days (Garvey 2014) and, indirectly, Xenophon’s Anabasis (L’Allier 2014); see generally Bataille (2014).

[23] The first Earth that the Colonials reach is a barren planet that has been destroyed by nuclear war. The second, inhabitable Earth is discovered only through the intervention of Thrace, who is implied to be an angel of “God,” the all-powerful being behind the events of the series that is identifiable neither as the Cylon God nor as the lords of Kobol. Thus Earth is finally attained through a non-Colonial spiritual force, but the mythic approach was necessary to get the fleet to the point where Thrace could intervene.

[24] On the subject of the series’ depiction of scientists, particularly Baltar, see Jowett (2008).

[25] Stoy and Kaveney (2010) have made the most vitriolic outbursts regarding the finale. Kaveney (2010) criticizes the series on the basis of his own definition of SF (“literature of reason, not faith,” 230) and on the notion that the episode was the result of lazy writers.

[26] A misunderstanding of this may lie behind the criticism of Stoy (2010): “the odd and ultimately pointless use of Greek and Roman deities to stand in for the Colonial ones . . .” (20). Although she never fully explains what she means by this, her comment suggests that she feels that classical myths were tacked onto a Judeo-Christian systemof religious practices without deep significance for the narrative or for the audience. Cf. Ryman (2010: 41): “The few concessions to [the SF] setting are inexpensive substitutes. . . . These fool no one; and are readable as jokes.”

[27] Six: “Don’t you understand? God is love” (Miniseries). Cf. 1 John 4:8: “God is love” (ὁθεὸςἀγάπηἐστίν).

[28] Marshall and Potter (2014).

[29] Joshel, Malamud, and Wyke (2001: 4); cf. Brown (2008: 416).

[30] Agathon is the first name of a Greek tragic poet of the mid-to-late fifth century b.c.e. It may resonate for a modern Western audience familiar with “Agatha” as a first name.

[31] See, e.g., Wills (2010: 130–31).

[32] A scene from episode 4.4 (“Escape Velocity”) makes the point that the Colonial/classical tradition is not enough to ensure humanity’s survival. Lily, a member of Baltar’s monotheistic cult, hesitantly reveals that she believes in Baltar and his one God as well as in Asclepius, the god of healing in both the Colonial and classical traditions. Head Six, a spiritual entity whom only Baltar can see, remarks, “Old gods die hard.” The Colonials’ gods die hard because they are an important part of the series’ teleology—and indeed, since Colonial society provided the basis for later ancient societies, as the final episode suggests, the old gods continue to live in different forms throughout human history.

[33] Moore paralleled Colonial civilization with the Roman Empire before its fall on his Scifi.com blog on 15 March 2005; this comment is no longer available in its original form. His notion of (American) society mirroring the past of the Roman Empire is common in SF (see Brown 2008: 416–422) as well as in early American thought (see Winterer 2002: 79); see the chapters by Makins and Kovacs (this volume, chapters thirteen and nine, respectively).

[34] This view of the legacy of classical antiquity is ironic since, according to Vernant (1982: 11), myths played a major role in enabling Greeks to create democracies that were based on materialist thought.